The other day, I went back to visit friends from high school, whom I hadn’t seen in about fourteen years, in the town I haven’t visited much since then. Why not, I can’t really explain.

It was one of the strongest experiences of sense-memory: watching the curve of the off-ramp come into view; feeling the curve in the tilt of my car; knowing when to slow down. Driving from the Putney Road strip into the little downtown: they’ve redirected traffic, one way past the Common now, so where I expected the stop sign I’d failed to stop at during driver’s ed.—with the bulldog-owning bulldog of a teacher jamming on the breaks—there was none. Past the library on the right, where I’d spent so many after-school afternoons. Down the slope.

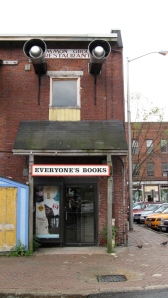

I can’t believe how much has stayed the same over the decades. The same businesses with the same awnings, not updated in twenty years. (The sign remains for the Common Ground, though the restaurant is no more. It was a true hippy spot: a cooperatively run restaurant, on the second floor, with creaky floorboards, a bottomless bowl of salad with great tahini dressing, and dense, buttery cornbread.)

Over other storefronts, new signs : shiny, with spiffy, computer-designed lettering, but keeping in the spirit of the town–a store selling natural body products, another new-age bookstore. I parked on Main Street, across from The Shoe Tree—there for as long as I can remember. Above those buildings to the left (east) I see the top of Wantastiquet, that huge hump of a mountain I’d walked up and down with these friends so many times, (and remember parking in its secluded parking lot at night), rising up abruptly from its foot in the Connecticut River.

I looked up Elliot St. and saw that familiar block between Main Street and the Harmony Lot, where we’d always circled slowly a few times before finding a spot. There was McNeill’s Brewery on the left, Maple Leaf Music on the right, where I had my first real job (lots of dusting and re-alphabetizing of sheet music). Just across Elliot Street, down the beginning of the steep hill to Flat Street, was the slanted storefront of Mocha Joe’s coffee shop, where I had my second, and probably favorite, job. Everything inside was exactly the same. Four steps down to the counter, display of Bodum pots, tea things, and tee shirts on shelves on the left, a little round table to the right, and the milk-sugar station, the high counter straight ahead. They were playing The Smiths. That sounds familiar.

I saw Shannon first at a table at the center of the same ancient-stylized floor painting of a bird’s head in a circular design. She looked like Shannon. She said, “you walked right past Ham.” He was at the counter. We gave each other a big hug. I was shaking! Shannon said she’d reached Amy, who had said she’d be here. We waited just a few minutes and saw her coming down the stairs, looking exactly like herself. She said, “I saw you on the street, and thought, yup, that looks like her.” It’s hard to express the feelings in all of our looks and hugs. We’d known each other so well, and then had been so far apart. We all felt as if we couldn’t explain why we’d lost touch. We stayed there for a few minutes and then walked down the hill toward the bridge to New Hampshire to the Riverview Café. We sat on the deck above the river, looking over at Wantastiquet—that mountain that figures so prominently in my memories of high school.

Our personalities were the same, though we were all more comfortable in our own skin, and talked more like adults, less like self-conscious teenagers. I remember all of their voices so well. And their laughs, mannerisms, bodies. It was like seeing distant cousins you used to know well, but more complicated. We didn’t do much reminiscing in part, I think, because our group memories weren’t always happy. There was also the feeling that we didn’t need to repeat old stories: the stories were in the air around us. We had so many shared memories, they were there in our looks more than our words. We had a decade and a half to catch up on. The fourteen years when we became “grown-ups” and made our lives what they are now.

One has traveled all over the world and lives in New York City, where he writes headlines for The New York Times; another lives in her childhood house, farms the land of Circle Mountain farm, and sells her organic eggs and produce to the locals; a third is a scientist studying the impact of climate change on different species, and on humans. I’m working on a Ph.D. in literature and writing a blog about local food, living in Alabama, and moving to Rome. All of these endpoints, and the paths that took us there, make perfect sense for who we were and at the same time seem paradoxically outlandish. When I told Amy my dissertation was about eighteenth-century British literature, we both started laughing. Shannon laughed at herself for knowing so much about the different beetles that are killing off the trees of New England. Hamilton laughed about having a job that feels like professional ADD, and Amy said, “I’m a farmer,” and we all laughed.

Walking with them, back up to Mocha Joe’s, where Ham went in for another coffee, and then up Elliot St. and around the corner into the Harmony lot, felt so familiar. My feet, legs, body, eyes remembered all of the little details: even the concrete sidewalks haven’t been updated. There was the little triangle of grass at the corner of the lot and the street that always gets trodden down to mud. The lot, and the back doors of old buildings leading to the same shops (The Book Cellar, Galanes’) were exactly the same.

As I drove up the hill, I remembered—in a deep mind/body memory—the little y intersections and nineteenth-century houses along the streets that led up to Western Ave. I took a right onto the interstate, but if I’d gone straight, the third right would have been Orchard Street, the hill I walked up and rode my bike up so many times, to Meetinghouse Lane, and home.

Incidentally, the food we had was mostly local: goat cheese salads, grass fed cheddar-bacon burger, pulled pork. We ate and talked. The hours went by, and we barely noticed.

Read Full Post »